Now, this issue we will go back in time to when I was designing and building theatrical scenery. One of the basic things that we were taught was how to build theatrical wagons. Wagons are rolling platforms. They are an essential component to scenery in the theatre. When they are built right, nobody thinks about them. But, when they are built wrong they are a disaster waiting to happen.

Unfortunately, not everybody knows how to build a wagon properly. This has been a source of aggravation since dinosaurs roamed the earth. It is all a matter of high school physics. If you don’t understand transfer of force you will not get the wagon right. I recall a phone call in the middle of the night from a local amateur theatre group. Their scenery was stuck on stage and nobody could move it. Huge sets were built on wagons, improper wagons, and it was all stuck because the wagon sides were jammed against the floor.

Why was this? Read on and you will see their errors.

I suspect that there are all sorts of modern technology available to make scenery wagons. Here we are going to look at the “traditional” methods and materials. This isn’t really a “how to” post. Instead, it is more of a “why wagons fail” treatise.

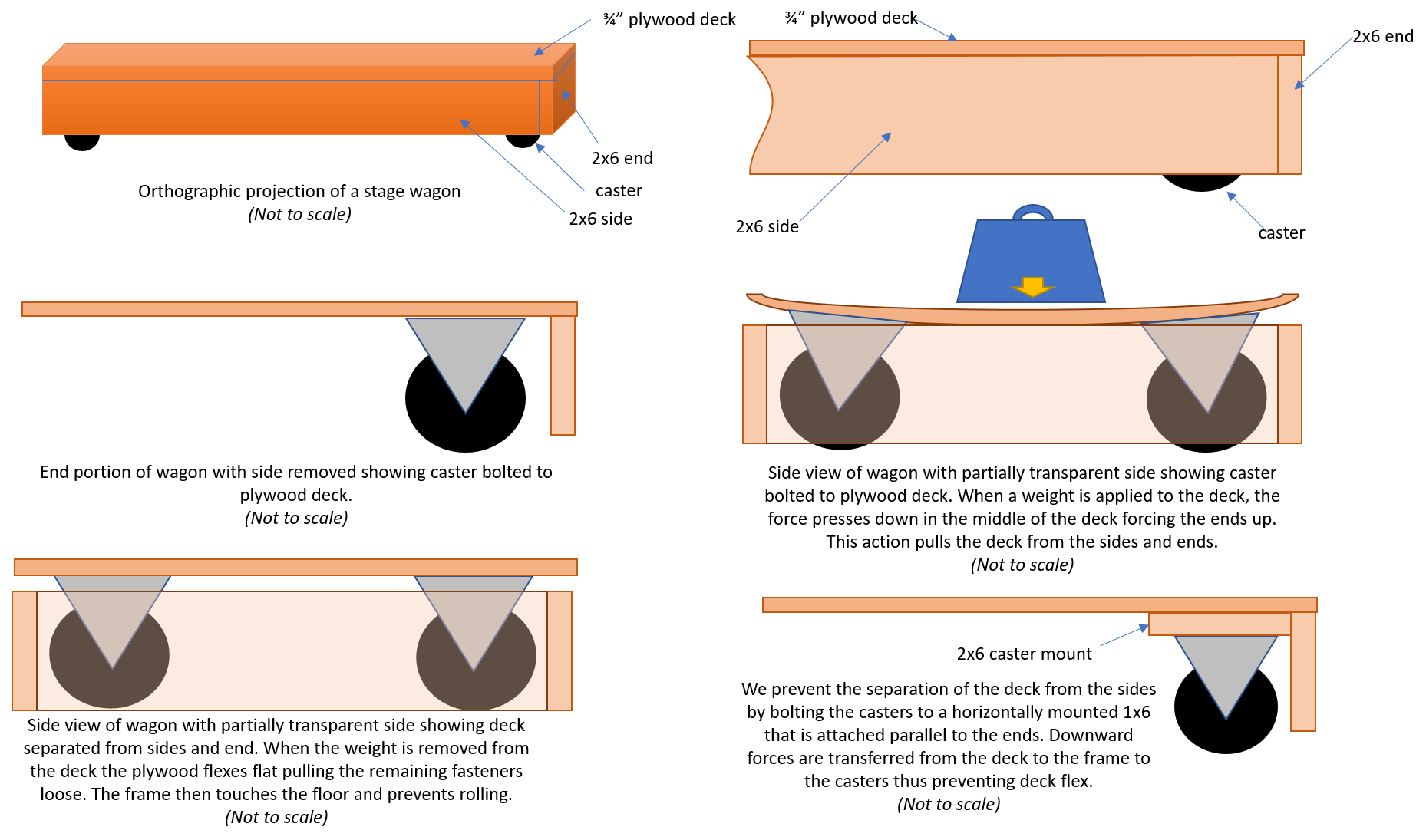

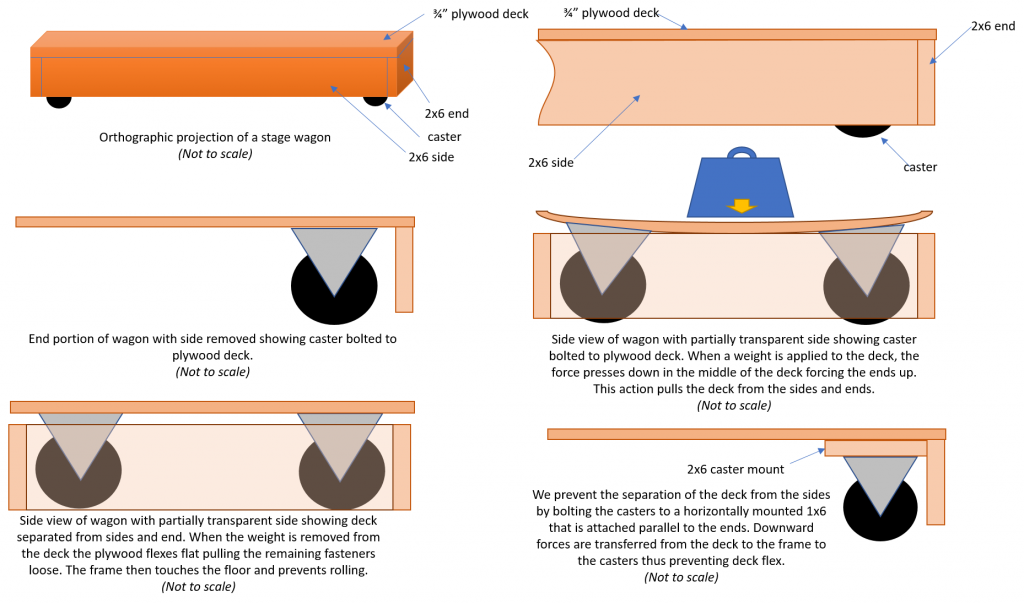

In this exercise, we are assuming our wagons have 2×6 sides and ends, and ¾” plywood decks. Lag screws connect the sides and ends at the corners. Wood screws attach the plywood. Nails are obviously worthless because they simply pull out in time.

The trouble starts the casters are bolted to the deck. Let’s say that we have a wagon 4’ wide and 8’ long. If we don’t have casters in the middle, that is a relatively long unsupported span. A weight, such as an actor, is placed in the center of the wagon. Gravity exerts a downward force that is transferred from the actor to the deck, then to the wheels, and finally to the stage.

In this situation, the wagon’s 2×6 sides and ends function only as stiffeners and provide little structural strength and no support. Worse yet, the weight in the center of the wagon causes the deck to buckle. The center goes down and the ends of the deck pivot up. The force of the buckling causes the deck fasteners to pull out of the 2x6s toward the ends.

When the weight is removed, as when the actor steps off the wagon, the deck tries to flatten itself out. The center of the deck wants to move up and the ends downward. We then discover that the fasteners that used to secure the deck ends to the 2×6 frame now hold the deck away from the frame. This causes the center fasteners to now pull out.

These movements are usually miniscule unless the weight applied to the wagon is excessive. But, if you can imagine performers and props being placed on a wagon and then taken off for rehearsals and performances over and over you can see that these tiny changes are enough to eventually cause the sides of the wagon to come loose and drop to the floor.

Indeed, that is exactly what happened to that amateur theatre group I mentioned before.

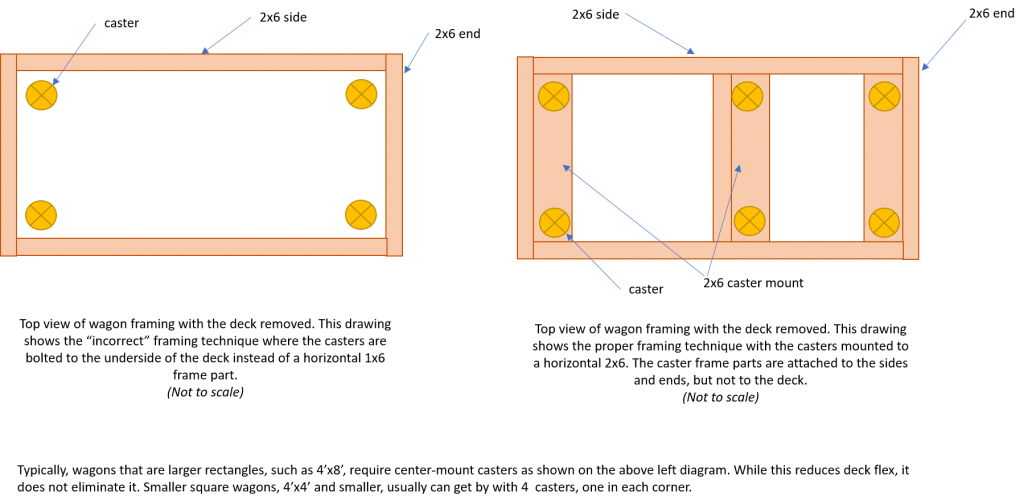

The prevention of this problem is to make sure that the transfer of the gravitational force does not cause the deck to buckle. In the diagram below you see that an additional 2×6 piece is added to the frame. It is attached horizontally, or “flat”, at the ends. Long wagons will also have such a piece in the middle. This piece is secured to the frame, but not to the deck.

The casters are attached to the flat 2×6 in the corners. When a weight is placed on the deck, the force is transferred from deck to the frame, then to the casters, and to the stage floor. The frame is structural and is rigid. There is no flexing of the deck, and that means the fasteners cannot work loose causing the sides to fall off. The 2×6 frame is now both structural and provided rigidity.

I have seen various attempts to prevent deck flexing and still bolt the casters to the plywood. The most popular is trick is to attach additional casters in the center of the wagon. While this does reduce the gross flexing, it actually introduces two additional buckles. In most instances, the sides will stay on longer, but they will eventually fall off. On top of all that, the sides still are not structural. I have worked with wagons over 20 years old that were in fine condition. They had never suffered a failure because they had properly attached casters. On the other hand, I have seen wagons that fell apart after only a couple of weeks because the casters were attached to the decks.

There you have it. This is how high school physics and force transfer must be considered when you build your scenery wagons.